Inhaltsverzeichnis

“I do everything for my husband…” said my client. Over and over again. Saviour mode: ON – and she didn’t realises it.

It was particularly important to her that those around her perceived her as “good”. That she is a helpful person. And that she was appreciated for it. She was completely caught up in doing something for others.

- Have your husband’s back? Of course.

- Bake for your daughter’s afternoon at school? Of course!

- Biscuits for all the neighbours and all the parents of the other children – different varieties: of course!

- Go shopping for the elderly lady in the house? With a word of honour.

- Clean your son’s flat every week and do the laundry? – That’s what you do as a mum!

- Take on overtime without being asked? – No question!

The list is long… and of course just one example of what she has taken on over the years without being asked or questioned. It happened “automatically” – as it always has in her life.

She wants to please (everyone)

To be the “nice girl”. The one everyone likes. The one who always helps. Always there. That’s what – socially speaking – is categorised as “good”: always helping. Always being there. That’s what the once little girl (and the boys) were taught. Being useful. Making yourself indispensable. To be helpful.

Hello saviour mode: Welcome to the drama triangle

Feeling indispensable and always being there for others may look good – but it’s not.

What plays a role here is the so-called “saviour mode” from the drama triangle.

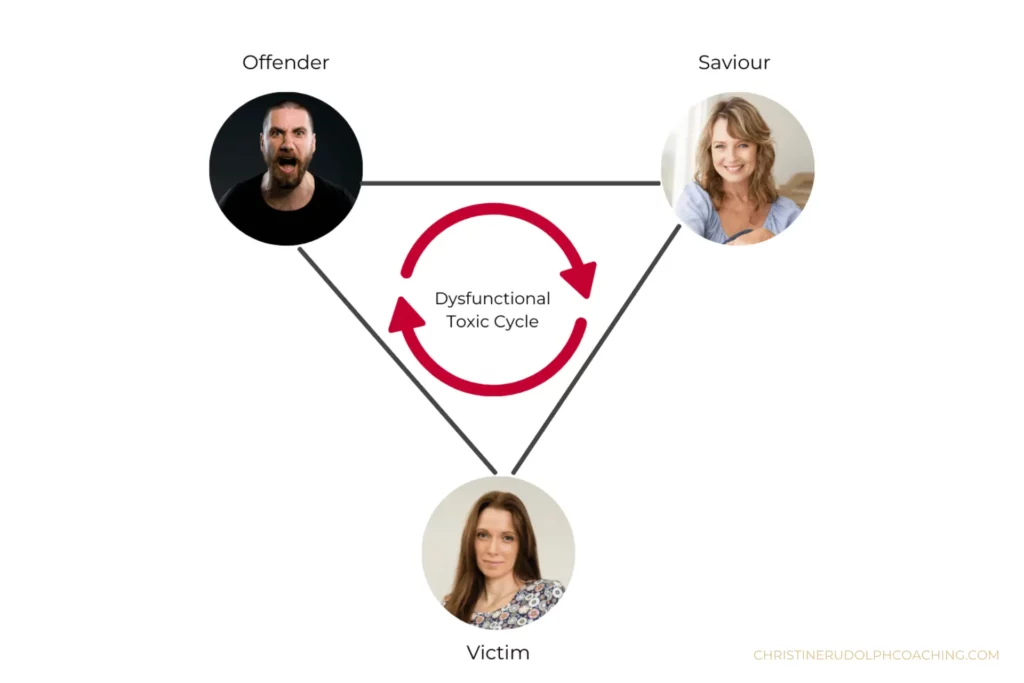

The drama triangle is a psychological model for (ineffective) human interaction and comes from transactional analysis. The model was described by Stephen Karpman. Dr Eric Berne, the father of transactional analysis, described it in “Games People Play“: Welcome to the “show.”

The rescuer mode is also known colloquially as the “helper syndrome” (this word was coined by the Munich psychoanalyst Wolfgang Schmidbauer).

In the drama triangle, there are generally three different positions that can be taken by either two or more people (if you’re not careful!).

- The perpetrator: he “does” something (usually from the “top down”)

- The victim: suffers under the perpetrator

- The rescuer: is always there without being asked

To make this dynamic easier to visualise: The most classic drama triangle is the affair. One person cheats (= perpetrator) and cheats on their partner (= victim) with their lover (= rescuer).

Basically, the positions change when interacting with other people and we can choose to take the position of the rescuer, the perpetrator and the victim. However, everyone has a so-called “favourite position” – the one that has been particularly familiar to them since childhood. He or she particularly likes to take this position.

We will concentrate here on the position of the (noble?) saviour.

He – or she – is fully automatically orientated towards helping. Fully automatic because this behaviour is automatic – i.e. without reflecting or thinking. You just do it. Always.

But why?

The underlying dynamic of rescuing and helping is the dynamic of gaining recognition – and escaping possible rejection by other people. If I position myself as a rescuer – I am always welcome. And my underlying fear of not belonging or being excluded from a community is calmed as a result.

The unconditional need to be accepted or to belong to a community is a deeply rooted human need from the “mammoth times”. Belonging to a group was our safety when attacked by others (or the mammoth). After all, we are stronger together!

This basic need is so deeply rooted in us that it is existential: a baby MUST belong to its mother and feel her with all its senses (physical/smell/touch etc.) (and thus have access to food and security), otherwise it will die.

In evolutionary terms, it is a matter of life or death.

The oldest part of our brain (brain stem) is the so-called reptilian brain. It represents innate behavioural patterns that are aimed at the primitive survival of the individual and the reproduction of the species. It acts as a control centre for unconscious, emotionless, automated behaviour patterns that are reminiscent of reptilian behaviour. In stressful situations , the reptilian brain takes complete and sometimes paralysing control over us: life or death.

Be my “hero”: Deeply rooted in women

The role of saviour can be found in many people, but it is often particularly deeply rooted in women. An important part of this is the social expectations and role models that have pushed women into weak, male-dependent positions for many centuries – and only projected the role of carer. From an early age, girls are usually brought up to be there for others, to care, help and offer support. Unselfishly, of course.

Later in life, this develops into a strong need to constantly “want” to be there for others – to have to (in order to be respected) – and thus to “save” them, often without being asked. Everyone else comes first and there is usually no time left for yourself. And often these people don’t even know what to do with “time for themselves”. They are always on the lookout, expecting to be able to do something for someone else.

The need to help overrides their own needs and goes beyond their own limits.

They are usually not happy with this. Even if they only realise it later. Inner dissatisfaction, usually suppressed – or noticeable as physical symptoms, inner stress and burnout – these are usually the signs of their own overexploitation.

The “Drug” saviour role: when helping becomes an addiction

There is a dangerous tendency towards addiction in the position of rescuer. It’s so easy to lose yourself in the role of the indispensable helper and forget that you also have needs that need to be met. The need to be needed, the striving for recognition and affirmation – acts like a drug and can degenerate into a non-substance-related addiction. Mostly unconsciously, people are constantly on the lookout for the next person or situation “in need of help”.

This goes so far that people are helped who have not even asked for help. Or, in tricky situations, you jump into the breach “like a fire brigade” as a noble ri(e)tter.

The crux of the matter: nobody thanks you. And the person you helped without asking often reacts harshly and avoids the helper in future. The rescuer addiction is treacherous because it is perceived as something positive. After all, you are helping others. How can that be bad?

However, what you don’t realise or even reflect on is what you are actually doing. On the surface, you are helping others. On a deeper level, however, you are crossing boundaries. Boundaries of other people. You are “imposing” your help, so to speak. That is crossing boundaries. Because the other person would (normally) ask if they needed support.

What happens then: Deep disappointment (= the end of the deception). You help and others are so ungrateful. Apparently.

Where do you forget to help yourself? Where would you rather not look? Why does your system project helping onto others?

Watch out for the trap: the dynamics of the drama triangle

The roles in the drama triangle are all treacherous. It’s easy to fall into the trap of constantly jumping from one crisis situation to the next as a rescuer, always ready to help. But what happens when there is no one left to rescue? Or if the help is not accepted and not wanted?

Then the drama triangle tips – and the rescuer mutates into a perpetrator. He becomes angry and unpalatable, complains about everything, tells others how it’s “right” and boycotts the relationship as a result. Or he becomes a victim. He ultimately feels overwhelmed with a deep sense of being taken advantage of. Because: the others don’t thank him for it (according to his thoughts and feelings).

EXIT the saviour mode: self-care and setting boundaries

To get out of saviour mode, it is important to become aware of your own needs and limits. What exactly do I need to feel good? I like to work with these questions:

- WHAT do I really want?

- What do I really WANT?

- What do I really want?

- What do I REALLY want?

Self-care is the key term here. You can supplement the question with: Is this good for me?

Metaphorically speaking, the journey is once again the destination. Because, of course, someone who has been in saviour mode for years cannot quit overnight. As I said, being used has addictive potential, as there are deep underlying issues: Being accepted for who you are (“I’m ok.”). Coming to terms with this takes time.

Getting out means taking yourself seriously. After all, the most important person in your life is yourself. Internalising this and learning to recognise and set your own boundaries – i.e. saying NO – is deep work.

If you like, I will be happy to accompany you. Online and here on the island. Gladly both.

Sincerely, Christine