Inhaltsverzeichnis

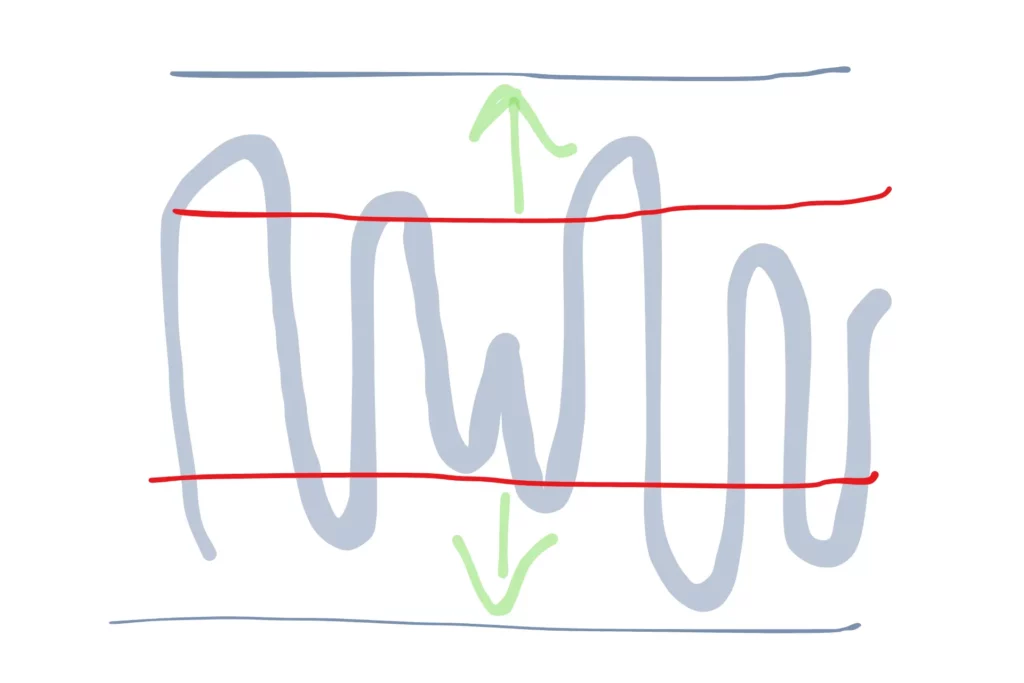

The most important resource on the way out of stress or burnout is our nervous system balance. If we imagine our nervous system as a scale in which we are either active (DOING – scale 1) or relaxed (BEING – scale 2) – when we are stressed or burnt out, scale 1 is simply too full – and tips downwards. As a result, there is no balance.

Scale 1 contains stress, anger, too little or no sleep, perhaps alcohol or other distractions, multitasking, answering everything IMMEDIATELY, mobile phone ALWAYS on, balance towards 0, jogging, yoga (what is that?), food: biscuits from the meeting and pizza from the chiller cabinet – sometimes a burger…

Ok, that’s quite an extreme scenario – and yet it looks – more or less – the same for many people. In addition, there is often pain that is anaesthetised with tablets.

Perceiving… Feeling… feeling nature… far, far away.

Being alive is in our cells

Emotions and feelings. They are usually lumped together. But it’s not that simple: they are different terms that we usually mix up in everyday language. But let’s start from the beginning:

Emotion and feeling are what defines our humanity – or rather our being as a living being. This is a clear criterion for aliveness. And not only that: emotion and feeling are located in our cells. And we have a lot of them! So when we feel joy, we feel it in and all over our body! When we feel sadness, it takes over us just as completely.

The properties of colours follow the changes in emotions.

Pablo Picasso

We cannot separate ourselves from our feelings and emotions. And yet – apparently – many people manage to do just that. People who no longer want to feel because it hurts too much or once hurt too much. These people push emotions away, suppress them or numb them (through work, sport, alcohol…). At a price: all these emotions and feelings come back: either they show themselves through the body or they break out like a tsunami at some point.

What are feelings and emotions?

Emotions are our immediate reactions to events or situations that we perceive as important or significant. They are usually intense and short-lived and can be accompanied by physiological reactions such as a racing heart, sweating or trembling. Emotions are universal and cross-cultural, which means that they are triggered and expressed in a similar way in all people, regardless of their cultural background.

Imagine you are walking home alone late at night and suddenly you hear an eerie noise behind you. Immediately you probably feel an inner turmoil: your heart starts to race, your hands get sweaty and you get goose bumps. This is the emotion of fear, which is triggered by a potentially threatening situation.

The reaction of fear is universal and cross-cultural. Regardless of where you live in the world or what cultural experiences you have had – so whether it’s Berlin or Denpasar – the likelihood is high that you would have a similar emotional reaction in a similar situation. This is because emotions are deeply rooted in our human biology and serve to alert us to important events in our environment (the mammoth, for example…) and motivate us to react. In this case, fear would prepare you to either escape the potential threat (flight) or face it (fight).

Like fear in this example, there are 7 basic emotions that American psychologist Paul Ekman has identified as such. These 7 basic emotions are:

- Joy

- Sadness

- Anger

- Fear

- Surprise

- Disgust

- Contempt

Feelings, on the other hand, are the subjective experiences and interpretations of these emotional reactions. They last longer than emotions and can be more complex and nuanced. Feelings arise when our brain interprets the signals coming from emotions and places them in the context of our personal experiences and memories. Unlike emotions, which are universal, feelings are deeply personal and can vary greatly from person to person.

Imagine you have just passed an important exam that you have been working towards for months. The immediate emotion you feel is joy or relief – an intense but short-lived feeling that might manifest in a big smile, a cry of joy or a feeling of lightness in your body.

But then there is also the feeling that develops from this emotion. You feel proud of yourself for the hard work you have put into the preparation. You feel grateful for the support you have received from friends and family. You may also feel optimistic and confident about the future now that you have reached this important milestone. These feelings can last longer and are more complex and nuanced than the original emotion of joy.

These feelings arise when your brain interprets the joy you feel – and places it in the context of your personal experiences and memories. They are deeply personal and can vary greatly depending on who you are, what you have experienced in the past and how you perceive and see the world around you. While another person in the same situation may also feel joy, their resulting feelings may be quite different.

Together, feelings and emotions form the foundation of our emotional experience. They influence our thoughts and actions, determine our relationships and interactions and play a crucial role in our well-being and quality of life.

If our emotions are given enough space, i.e. we can express them as we feel at any time, then we are in the so-called emotional tolerance window.

Imagine the sea lapping back and forth in a light breeze on a beautiful summer’s day. Very relaxed, very easy. Everything is “within the normal range”. No abnormalities.

However, if a heavy storm comes up – or even just a stronger wind – the waves get higher. And sometimes they spill over the parapet.

As a nice image for your nervous system: Whether even the strong wind is enough or only the storm is enough to make the waves overflow the shore depends on how much room for manoeuvre – i.e. tolerance – your nervous system has. This, in turn, is the result of personal imprints and experiences.

If you are positively excited, your nervous system is at the upper edge of the tolerance window. And if not… you may be annoyed that your boss has not asked you to a meeting, for example, even though you are responsible for the topic – and are supposed to accompany and implement the decisions from this meeting. A healthy reaction to this would be to ask your boss for a meeting, explain the situation as you perceive it and also express your healthy anger about it to him.

Perhaps he wasn’t aware of it and he can – just as healthily – react to your perception and apologise to you appropriately. To put it bluntly, this would be healthy communication in which the person can express their emotion (anger) based on a perception (without fear of it!) – and the other person in turn can take up the issue and clarify it (and thus maintain the relationship).

In this example, the emotions are within the tolerance window. The anger is there, but it does not spill over into rage, nor does it take the form of suppressed passive aggression (in the form of subliminal comments, deliberate failure to act, etc.).

But what happens when emotions spill over – or are suppressed?

When unfelt sadness turns into depression and suppressed anger into rage or even uncontrolled rage? When disappointment and suppressed sadness turn into frustration, which at some point is anaesthetised with addiction (work addiction, sports addiction, alcohol addiction…)?

In this case, the emotions have spilled over your own tolerance level – or may even do so permanently because your personal tolerance window has become smaller due to hurtful and traumatic experiences. This means that our nervous system is “less able to cope” and people are quicker to do a 180 or “tick off super fast” or are always busy (distracted) – they can’t calm down.

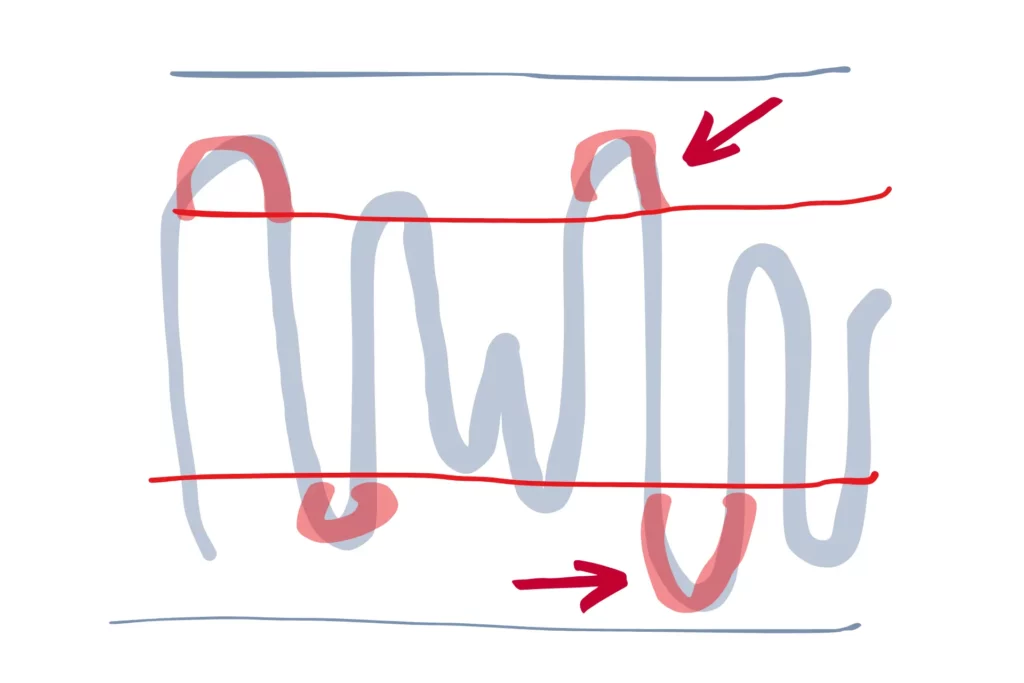

If the tolerance window tilts UPwards, panic attacks, sleep disorders, psychosomatic complaints such as shoulder/neck/back pain or even ADHD are located here.

If the tolerance window tilts DOWNwards, inner emptiness, depression, memory problems, post-traumatic stress, dissociation (feelings of numbness, no longer feeling anything, “phase-out”) and also feelings of guilt and shame are prevalent.

Trigger alarm

The tolerance window, in which it swings along in a “cosy and relaxed” manner, is narrower – and no longer offers much leeway with certain triggers. For example, where other people may react in a completely relaxed manner or at most get a little angry, you freak out completely.

A trigger is a “sore point” of a person. It can be a word, a smell, a certain part of a song, another person’s behaviour (a very simple example: an open tube of toothpaste)… In short: anything can be a trigger for someone.

What happens now – and this happens very often in couple relationships – is that you “dance” around this trigger. In other words: you know the other person’s trigger – there was an argument at the time – then it wasn’t talked about again – and now… the partner avoids this trigger (at all costs).

Although this is meant lovingly, it doesn’t help either of you in the long run. Because: the trigger remains (and is not dealt with). In other words, you move next to each other like “walking on raw eggs”. Of course, this also applies to everyone else – and not just in couple constellations.

The nervous system is dysregulated

Roughly speaking, the nervous system consists of two main actors, the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. The sympathetic nervous system is active in daily life and ensures that we can react appropriately to external actions in the environment.

The parasympathetic nervous system is responsible for relaxation. It regulates digestion (which only “works” in a relaxed state, for example).

Both players are essential for us: healthy tension – and healthy relaxation.

However, as we tend to be “driven” in our form of society (from one meeting to the next, quickly this, quickly that, and multitasking too…), our nervous system is basically in sympathetic utilisation – and rather un-relaxed. Couching in front of the TV in the evening is also not relaxing – but rather tense for our nervous system (even if you fall asleep in front of the TV, your nervous system is active if there is noise in the background or even a thriller is playing!)

The constant tension and, if necessary, additional stress lead to the nervous system not being balanced. Dysregulated.

So it’s already at its limit anyway – and if one little thing comes along (the so-called “straw that breaks the camel’s back”), then your reactions are no longer “within reason”, but more violent. Depending on where your personal tolerance range lies.

The concept of the tolerance window, or more precisely the “window of tolerance”, comes from trauma research and was developed by Dr Dan Siegel, Professor of Clinical Psychology. It describes how each person reacts personally under stress, depending on the size of their personal window of tolerance. This refers to the optimal range of arousal within which we are able to respond effectively to our environment and cope with stress. Within this window, we can regulate our emotions and reactions appropriately and are open to learning and growth.

However, when we are pushed out of this window by too much stress or traumatic events, we can fall into states of hypo- or hyperarousal (the red lines in the image above). In hyperarousal, or overexcitement, we feel anxious, panicky or out of control. When we are hypoarousal, or under-excited, we switch off, feel empty, depressed and dissociate: we no longer feel anything.

Understanding the window of tolerance is particularly important if we want to learn how to deal with our emotions. By learning to stay within this window, or move back to it when we have left it, we can better manage stress, regulate our emotions and ultimately build healthier relationships with ourselves and others.

It is therefore essential to regulate and balance our own nervous system and to expand our window of tolerance step by step in a healthy way.

This is particularly important for people coming out of years of stress or stressful situations, for people in burnout and with many fears and, of course, for people with (developmental) traumas.

How can I create a healthy nervous system balance?

Once you realise that, for example, excessive stress ultimately affects your nervous system (and therefore your whole body and every cell), it is clear how small exercises and routines can have a calming effect on the nervous system.

The simplest exercise to calm the nervous system is to make your bed in the morning. Brew a coffee. Take a walk in the park.

Sounds strange? Sounds simple. But it usually isn’t at first (because most people are still in Duracell bunny mode at the beginning (with hyperarousal) or completely depressed.

That’s why it’s so simple and yet so difficult: make your bed in the morning. This little daily routine gives your nervous system the impulse that all is well. People need their little anchors.

In order to slowly expand the “window of tolerance” and to be able to deal better with stress, these 8 practices are very helpful:

- Presence, mindfulness and meditation exercises

- Regular physical activity (walking, yoga, dancing…)

- A healthy diet and good water

- Sufficient sleep (parasympathetic nervous system!) of at least 7 – 8 hours

- Create space for emotions through self-care (diary, conversations with friends, coaching or therapy)

- Breathing exercises

- Being and perceiving mindfully

- Professional support from a therapist (with trauma experience and tools such as EMDR)

I know how difficult it can be to take the first step – and to seek support. Yet this is the most normal thing in the whole world: to seek help if you have taken too many wrong turns or simply lost your way.

If you have decided to take care of yourself (again) and to find your inner balance – with a clear focus on the new – then you are very welcome to make an initial appointment with me.

I look forward to meeting you.

Christine